Not commonly thought of as a dangerous occupation, baseball does have its professional hazards. None more so, of course, than a solid-cored sphere approaching your head at what looks like meteor speeds from 60 feet away. But there’s also an ever-present danger of your body being in motion at top speed and crashing into an unawares colleague or opponent moving just as rapidly.

Through the fingertips partially covering our eyes, today we look at some of those calamities on the field that resulted in bodily harm. Whether shaken up momentarily, or carted off the field on a gurney, these players all endured corporal trauma when all they wanted was to just do their jobs.

Though these on-field mishaps would seem to be capricious accidents, occasionally a player emerged who made his reputation as much on violent interactions with objects in the field of play as his talent for playing the game. Pete Reiser of the Dodgers illustrated this notion with his penchant for continuing to chase a fly ball until crashing into the outfield wall.

This lack of respect for the immovable object cost his career dearly. The N.L. leader in WAR in just his second season in 1941, he gave the next three years to serving his country. Upon Reiser’s return to baseball in 1946, his dazzling early success eluded him.

He was still a quality player, but his spectacular streaks across the field were no longer reflected in his numbers. And then, for one last time, his breakneck style fractured his skull, with the injury being so severe that he was read his last rites at the hospital.

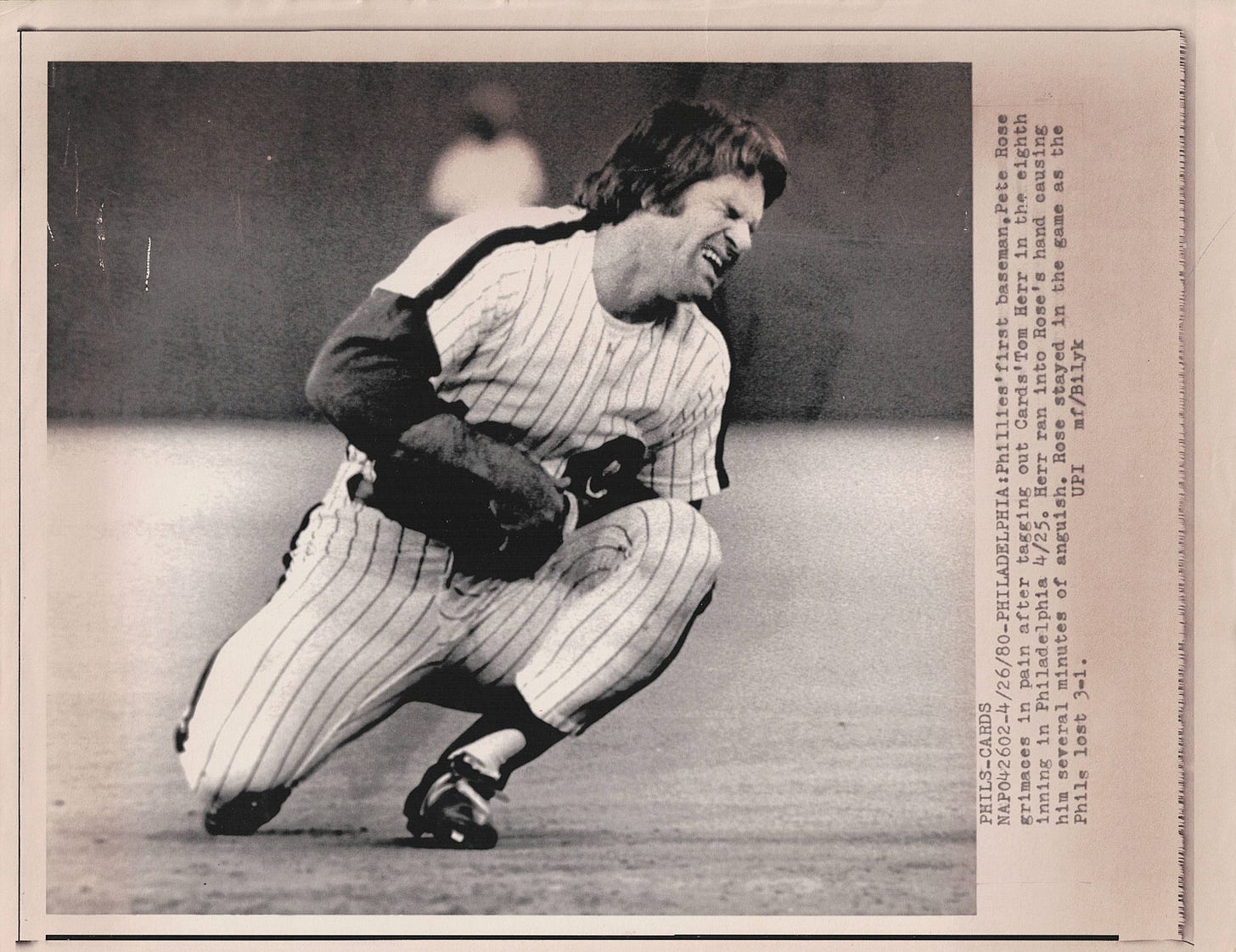

Pete Rose suffers an owwy after the Cardinals Tom Herr clipped him on the basepaths

Goose Gossage wanted no part of a Penguin dining near his dish in the 1981 World Series and sent him to the hospital room before he could sup.

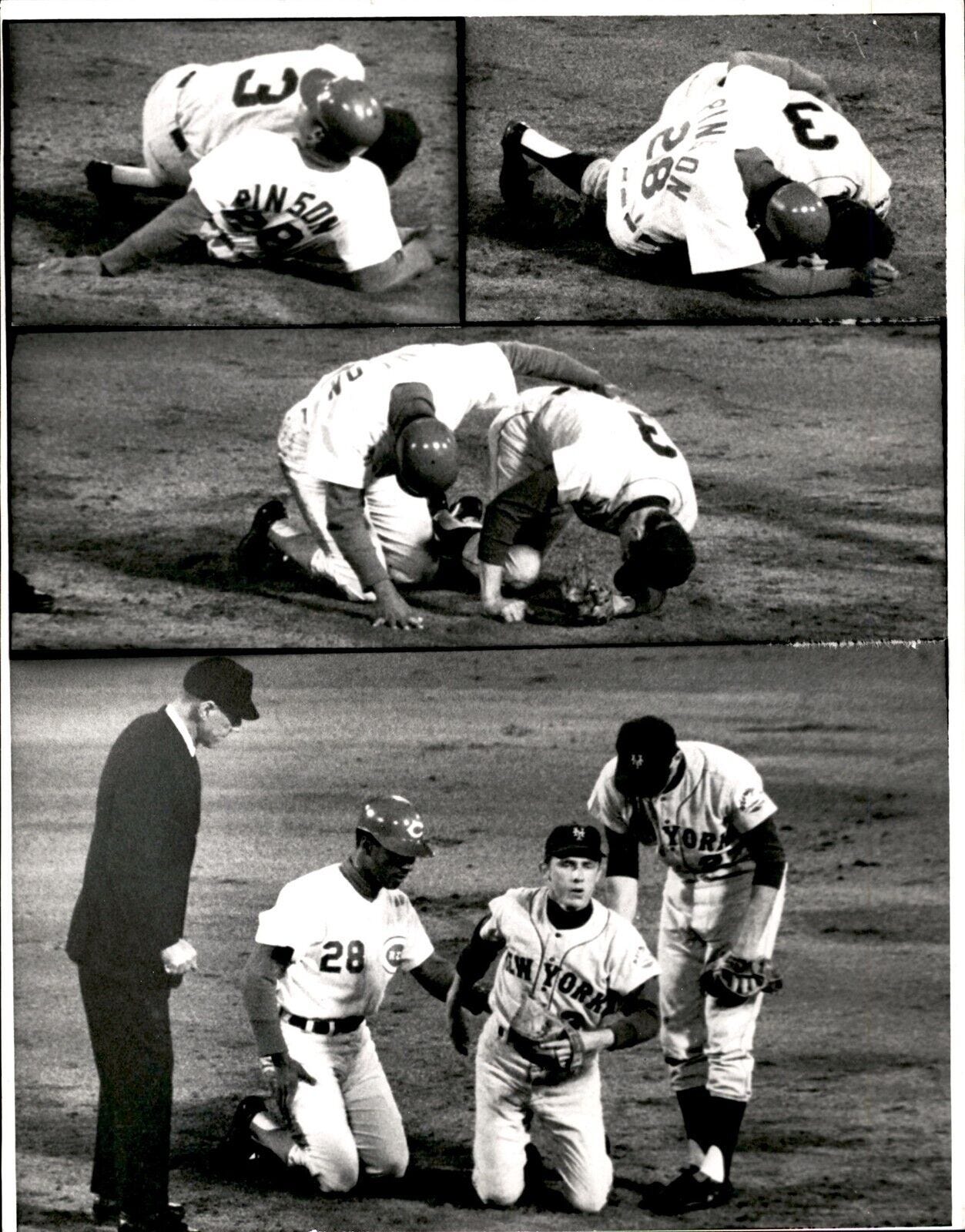

What appears innocent might not be. Danny Cater of the Phillies looks behind him as he rounds third, realizing he clipped Ron Santo in the head with his elbow while running the bases. But a closer look reveals that the Cubs shortstop is waiting for a harmless infield pop up to come down. Very strange for runner and infielder to come so close together on such a play. Santo was reviled in those days for baiting opponents and Cater, playing in just the first month of his career, could easily have been the recipient of some of Santo’s invective. Pure speculation, of course, but might his look backward have been to make sure the dirty deed was done?

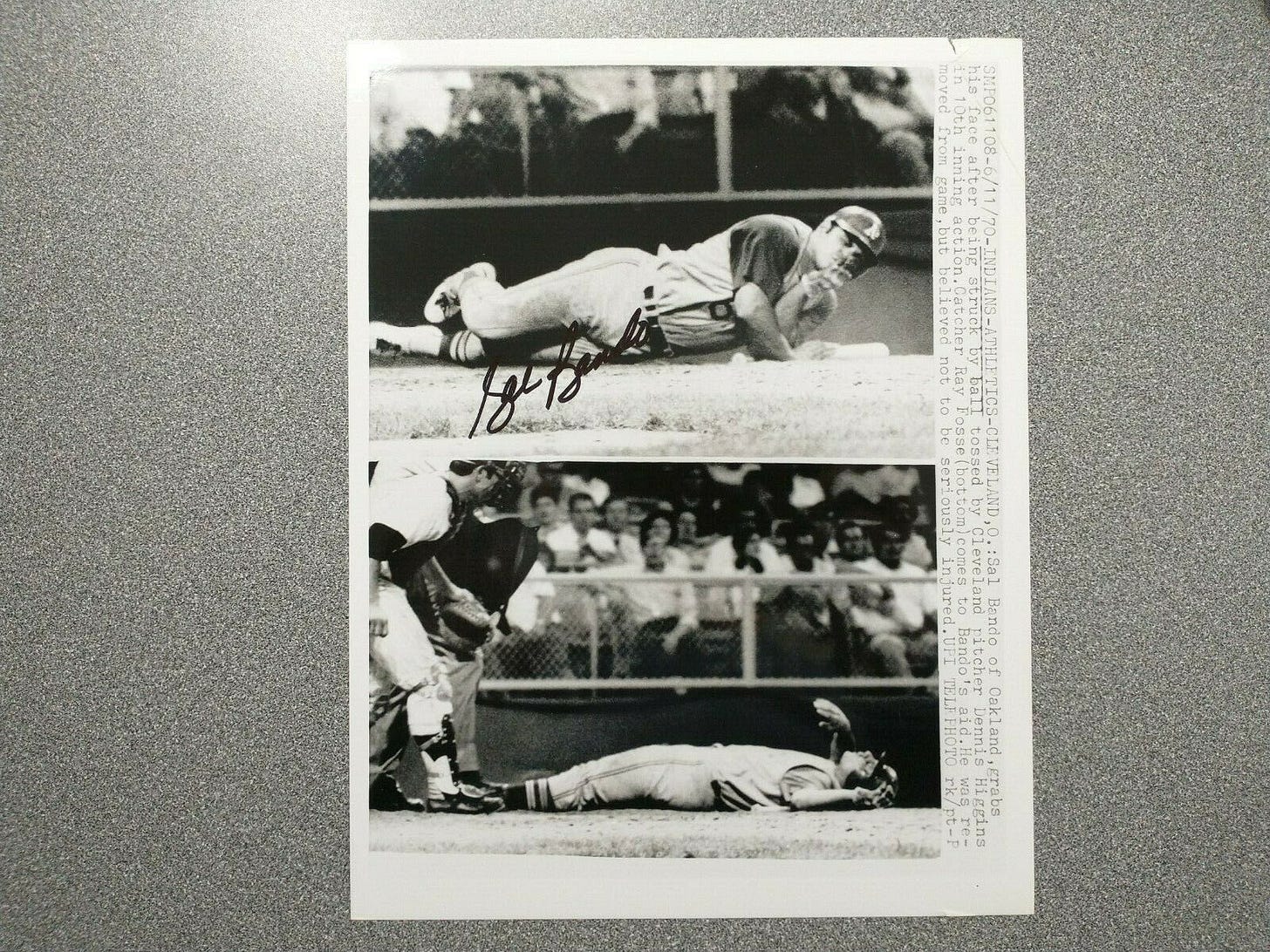

Sal Bando holds his face after being drilled by a pitch in 1970 and then rolls over on his back to collect himself.

Middle infielders are instructed at an early age how to avoid being spiked at second by players well-aware of the concealed weapons they carry on the soles of their feet. The Braves Sonny Jackson gets slashed on the knee, as can be seen by rip on his left pantleg.

Tom Seaver first missed action in 1974 due to discomfort experienced in his sciatic nerve, which is located in the lower part of the back and can send pain down the back of each leg when irritated. Though this shot is from two years earlier, it’s not unreasonable to think the condition has its origins in that moment.

Five years before Pete Rose came after him in the 1973 NLCS, the slight-of-build Mets shortstop Bud Harrelson had to contend with another Reds stalwart charging in hard at him. But Vada Pinson took the aftermath to a more salutary level when he immediately sought assurances that Harrelson was OK.

Only one first base in the big leagues and it can get crowded when one of the feet vying for position on it belongs to a Moose.

The beanings aren’t limited to home plate, as Mickey Mantle painfully experienced when a throw from Nellie Fox nailed him in the head as he attempted to get back to first on a line drive.

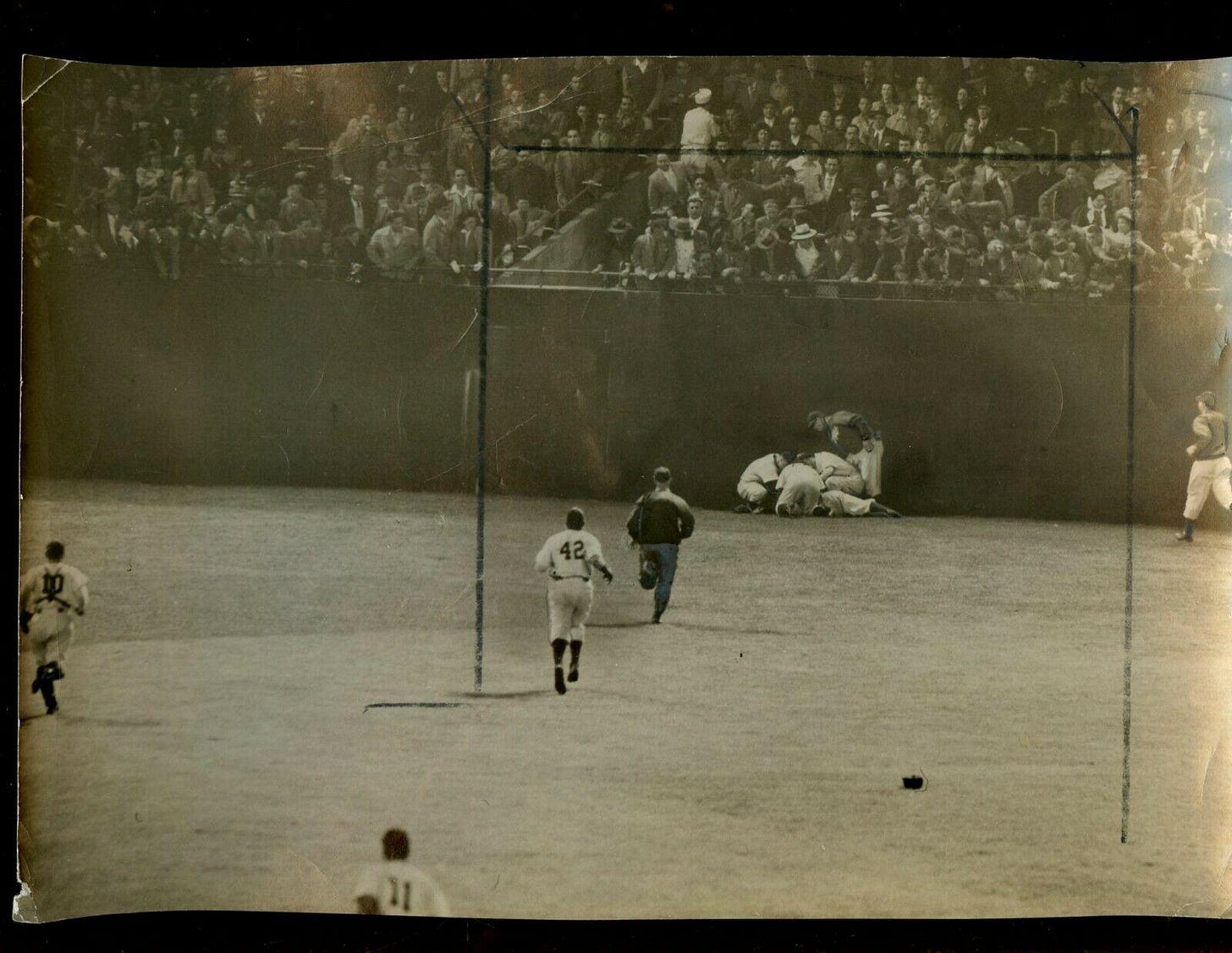

In most cases, an injury on the field is only apparent to the spectator in its aftermath. The beanings don’t carry a sense of dread for the viewer — they’ve happened before you can see it coming. Spikings on the infield occur on the microscopic level. Pitchers walk off the mound seriously injured, but you’d never know it from watching their last pitch.

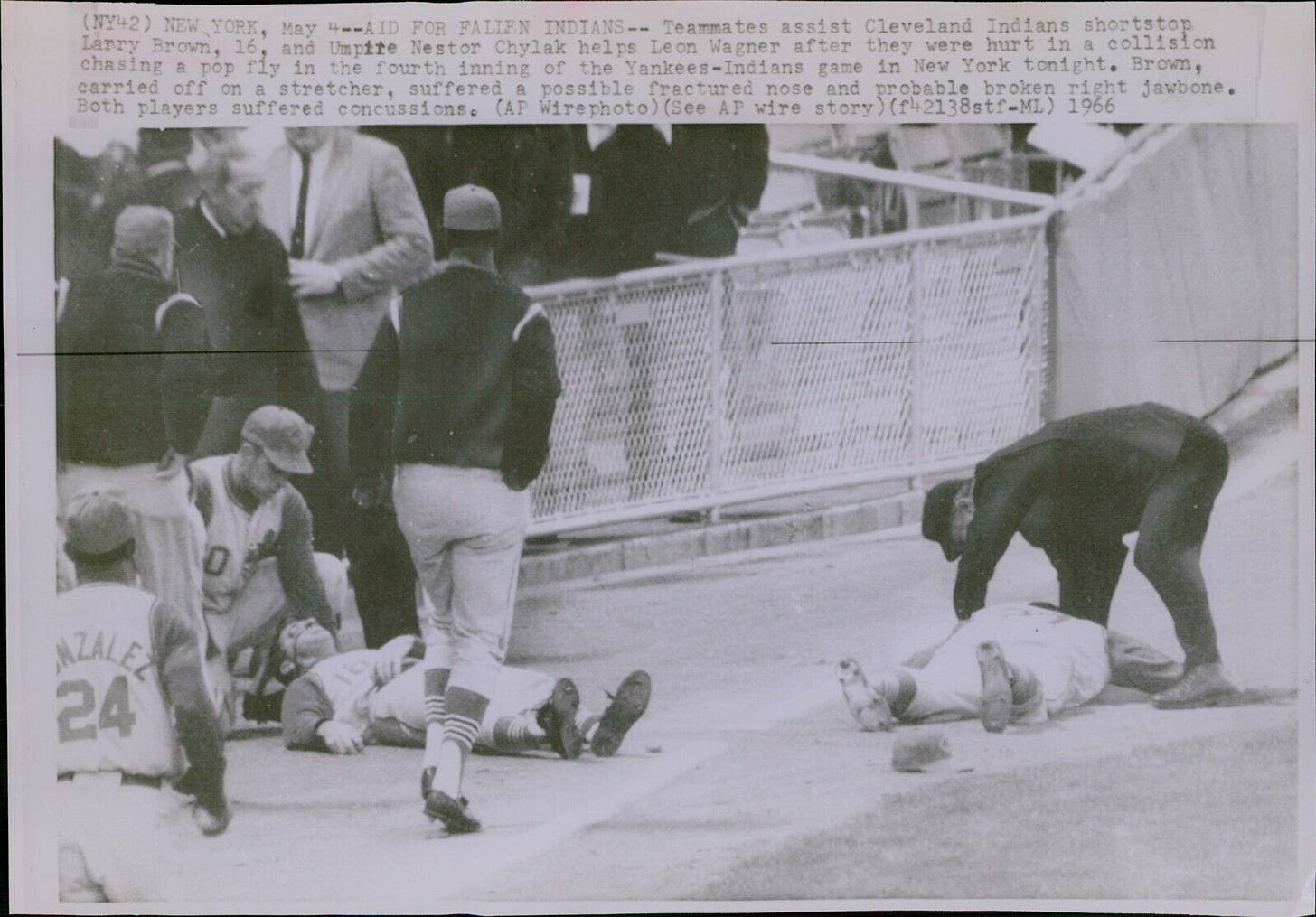

The one exception is the outfield collision, when the naked eye carries the capability of processing two bodies converging on each other at full speed and can anticipate the carnage moments before it occurs. If you’ve seen one of these in person, you’ll never forget it. If you’ve experienced one of these in person, you might have a freshly minted recurring nightmare to deal with.